Chornobyl (according to the Ukrainian spelling) is the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster. On April 26, 1986, a power plant reactor exploded and nearly poisoned a large part of Europe. Until recently, I didn’t realize how much my knowledge about the disaster was filtered through pop culture. I’ve learned about Chornobyl from two kinds of sources: dark tourism documentaries and HBO’s 2019 miniseries Chernobyl.

Then, last month, I shared a train compartment with a young IT professional, Nastya, whose mother mother grew up in Chornobyl - or rather the town next door called Pripyat. Nastya’s mother was fifteen in 1986. A few days after the accident, her parents packed their two daughters onto a train and left. Nastya was born in Kyiv, where her family lived after the accident.

But she has visited Pripyat, including her mother’s childhood apartment. She paid for one of the official tours that go around the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, and a professional guide took her right into her mother’s bedroom. What did Nastya find there? Why did she go? Is she glad she went on this Chornobyl disaster tour?

Nastya’s family is a Chornobyl survivor, and yet like so many tourists before her Nastya paid to get a firsthand encounter with disaster. What can Nastya teach us about the controversial practice of “dark tourism?”

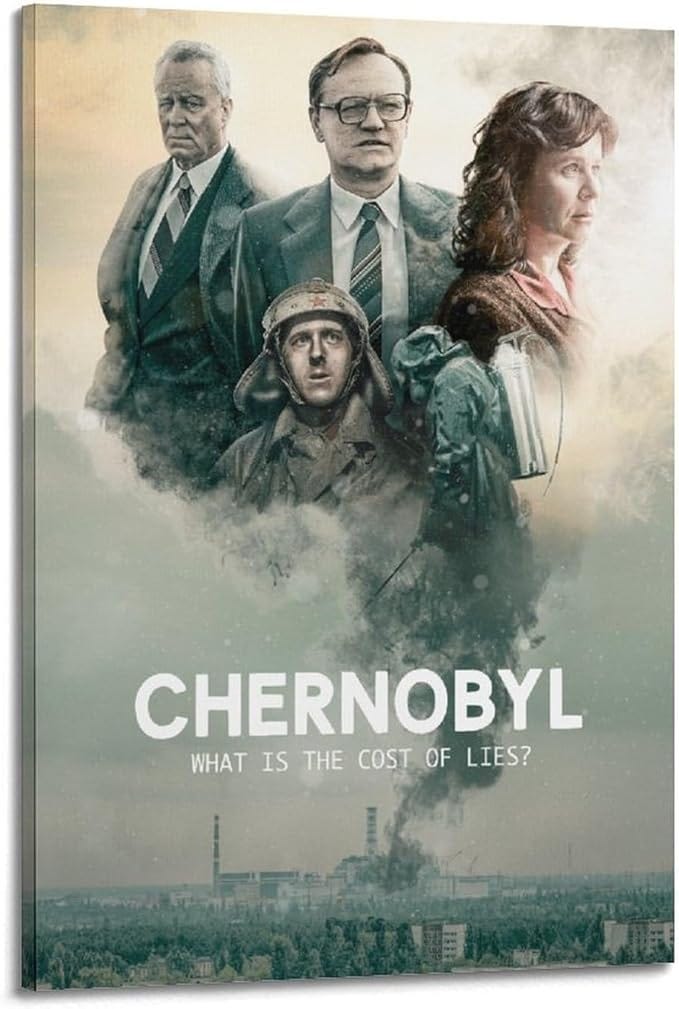

Chernobyl is a Hollywood horror flick

The acclaimed HBO miniseries called Chernobyl (according to the Russian spelling) focused on the political struggle behind the post-disaster cleanup. Reviewers praised the show’s philosophical reflection on the nature of truth. Others hailed it as a climate change allegory about the politicization of scientific fact. It’s also like The Handmaid’s Tale: Another HBO production that allegorizes political authoritarianism.

I disagree with all three characterizations. What is Chernobyl? It’s a horror masterpiece.

This becomes clear if you close your eyes and listen to the show. In crucial post-accident cleanup sequences, the soundtrack is all Geiger clicks and static, screaming pipes, and monstrously dripping water. The portrayal of everyday life in Pripyat also had a ominous quality, even though it was historically accurate, according to the critic M. Gessen in the New Yorker.

Gessen, who grew in 1980s Soviet Union, praised the production design’s “uncanny precision.” “Clothes, objects, and light itself seem to come straight out of nineteen-eighties Ukraine, Belarus, and Moscow,” they wrote.

But listen to the soundtrack and the precision and accuracy is less impressive. In Episode 1’s closing shots, Pripyat schoolchildren skip happily to class while ladies on a park bench chat. Behind the noise of the laughter and conversation, we hear a metallic pulse that echoes the plant’s emergency alarm.

Of course, this was physically impossible. Chernobyl was thirty kilometers away; no one in Pripyat heard the plant’s alarms. But we’re meant to have a sense of omniscience, the same kind of all-knowing awareness used in cheap horror flicks when the camera revels that the killer is waiting behind the bathroom door. Meanwhile, the doomed lead reaches for the doorknob.

Chernobyl’s soundtrack makes us feel, as we watch the ignorant people of Pripyat, both terror and pity. In the end, Chernobyl’s creators were sacrificed historical accuracy for Hollywood horror effects.

Having lived in Romania, amid the detritus of Communism, these scenes also provoked my sense of irony. I have spent time surrounded by the waste that, in the 1990s, neoliberal capitalism made of Communism’s material culture. This includes the clothes and objects that, as M. Gessen says, the miniseries so faithfully reproduced. Of course, the material culture of everyday Communism, didn’t have to become trash. In just five short years, the West’s vulture-like neoliberal economic planners would descend on this region. They carried promises of freedom and wealth; but they also told the region’s cowed and gullible political elite that, first, this material culture had to go. As I watched Chernobyl, I recalled that these school outfits would soon end up in dustbins.

Chernobyl’s creators, when they imagined pairing menacing music with images of Pripyat everyday life, didn’t actually have this particular tragedy in mind. They were more interested in crafting instructive allegories for Western audiences than exploring the ironies of political economy and the collapse of Communism. In Chernobyl, we know there’s nuclear fallout in the air, settling on Pripyat as people go about their regular lives.

In their Chernobyl review, M. Gessen complains that there are so few main characters from Pripyat. “We hardly see any of the evacuees at all,” they write. The one exception is a Chernobyl firefighter’s wife named Lyudmilla Ignatenko. Her husband was exposed to radiation at the plant. The show follows Ignatenko, pregnant with her first child, while she cares for him. Our last glimpse of Ignatenko is sitting and staring into space in the corner of a maternity ward.

“Following the death of her husband and daughter,” we learn in the epilogue, “Lyudmilla Ignatenko suffered multiple strokes. Doctors told her she would never be able to bear a child. They were wrong. She lives with her son in Kyiv.”

The epilogue goes on like this about the show’s other characters. It’s just a litany of who lived or died. If they died, we learn when and how. It’s like the science - the radiation, that is - is the only thing that matters about these people’s post-Chernobyl lives. Everything is reduced down to a question of life-or-death. Will we survive or won’t we? If lies incur a cost, the only cost that matters - according to Chernobyl - is death.

Nastya goes to Pripyat

The epilogue text is accompanied by a hymn, “Vichnaya Pamyat,” composed by Icelandic musician Hildur Guðnadóttir. Vichnaya Pamyat means “memory eternal,” the phrase used to conclude an Eastern Orthodox funeral. Orthodox worship services have no musical accompaniment. Guðnadóttir followed this convention by composing her Vichnaya Pamyat as a choral chant. (It is performed by Ukraine’s Homin Lviv Municipal Choir.)

Writing about Guðnadóttir’s work for Chernobyl, reviewers use words like “haunting” and “surreal,” as well as “heart-wrenching” and “mournful.” The critic Edward Bond writes that Vichnaya Pamyat captured the “bewilderment” and “grief” that Pripyat’s residents felt after the nuclear disaster.

But while I was speaking with Nastya about the Chornobyl tragedy, I didn’t sense this kind of interminable melancholy.

Growing up, Nastya told me, she’d heard about Pripyat; her mother and aunt had actually visited the abandoned town. Later on, journalists had come to her apartment and recorded her mother’s stories about life in Pripyat as well as what they’d seen on their return visit. (This was probably part of the oral history research project by Serhii Plokhy. Plokhy’s project became a 2018 book, Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe.)

In her twenties, Nastya had decided to go on her own. She signed up for a paid tour with a guide who takes people - mostly international visitors - around the Chornobyl zone of exclusion.

“I had wanted to go all my life but my mom said, ‘No.,’” Nastya recalled. “She said, ‘Not until you’re 18 at least. Not until you’re an adult.’ She realized that if I go somewhere or touch something, it could hurt me.”

Nastya went with a group of coworkers who were also interested in Chornobyl, but for a different reason. “For them, it was like an educational trip. They wanted to spend time together but not at some kind of work party. They learned some history.”

The guide led Nastya right to mother’s old building. “I only had my address and an apartment number. But I was with a guide who knew the place much better than me. And he helped me find the apartment.”

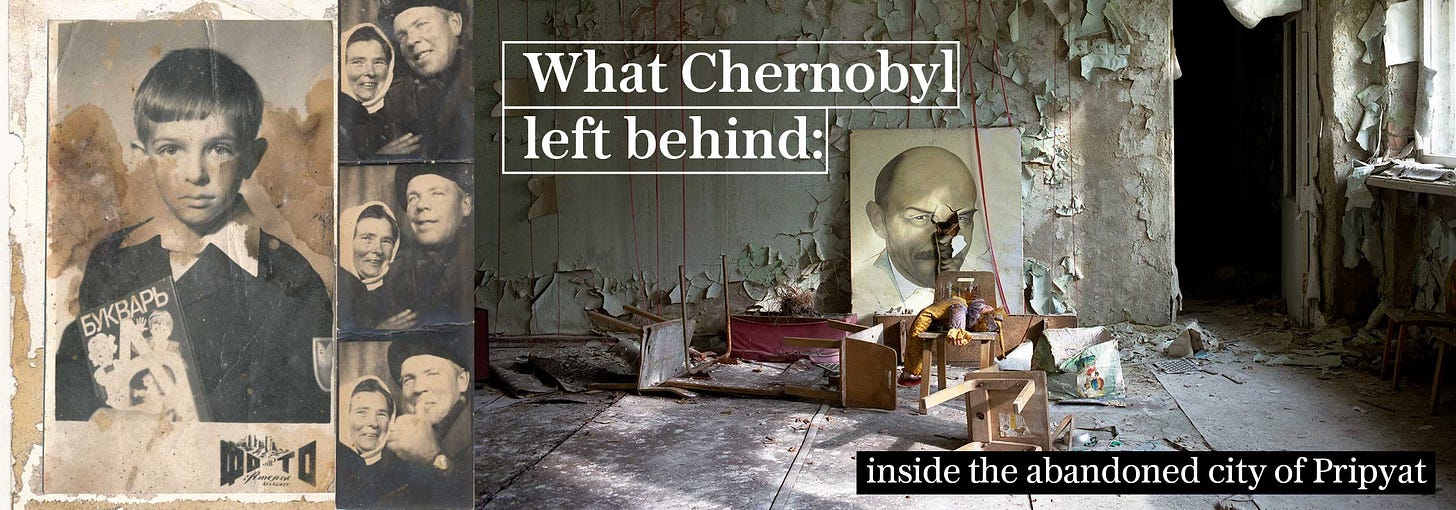

I expected Nastya to tell me about going into the apartment to find objects “preserved in time” - former residents’ abandoned belongings - that always seem to be the focus of tourists’ videos.

“You saw your mom’s stuff, right?” I prompted her.

“Well, kind of,” she demurred. “There wasn’t much of anything left at that time.

“My aunt had a poster of some Indian actor in the bathroom behind the toilet. She found this poster! It was there even after many years. But when I went there it was gone.”

When her mother and aunt had visited, they’d come back with stories about seeing their old poster of an ‘80s heartthrob. But Nastya couldn’t find these mementoes.

“What happened to it?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Nastya said, “I didn’t see it on the ground. Maybe someone came and took it? Maybe I forgot what my aunt had told me?”

“So what kind of impression did you get?” I prompted again.

“It was like a life that I could have had. It was such a different life. But it could have been mine. I love Kyiv. It’s our capital, of course. It’s our oldest city and greatest city. But what if everything had been right and good and okay? How would we be living?

“Also, the apartment was so small!” Nastya exclaimed. “I was so surprised. They were living there, two adults and two kids. It so tiny. But they were happy there.”

Family obligations, lost youth

Nastya had seen the Chernobyl TV show and even discussed details from it with her mother. (“The birds dying and falling to the ground is real!”)

Her mom’s accounts of teenage entrepreneurship and small-scale independence had left an impression. For example, her mom made pocket money doing family chores and spent it at a nearby mall on snacks. Nastya’s tour guide took her right up to the mall’s front doors, where she stood and pondered her mother in this place. “This is where she was happy,” Nastya told me.

These stories ended up distracting Nastya from the TV show’s intended allegorical meaning. “I realized that for my mom, specifically - not for all people but for my mom - this story is not about catastrophe. It’s not about what happened, whose fault was it, what happened at the plant, and all this stuff.”

“What is it about, then?” I asked.

“It was about her own life. She was a teenager. Life changed too much, so suddenly. She was very sad afterwards. It was overwhelming.”

Nastya’s aunt recalled not leaving things behind - abandoning their part of Soviet material culture - but rather what people brought. Some residents took extreme measures to fulfill family obligations: “And there was one family on the train leaving Pripyat, they were carrying their grandmother’s body. They didn’t have a chance to have a ceremony and bury her in a grave.

“My aunt felt this shock from seeing that,” Nastya explained, “It had a very deep impact on her. Throughout her life.”

It is difficult to know how Nastya’s tour of Chornobyl had an impact on her mother and aunt. Did Nastya’s presence at the mall give her mother a new opening to share her sadness? Did it open up a new way for mother and daughter to bond over the loss of a burgeoning adolescence? For Nastya’s aunt, did she gain some kind of emotional distance from the frightening encounter on the train? I didn’t ask Nastya these questions, and I probably won’t be able to because I’ve since lost her phone number.

But it’s possible to talk about what the experience meant for Nastya. For Nastya, it was about the universal need to test boundaries, a need that does not necessarily go away as once ages out of adolescence. She was in a place that was forbidden to her, and physically crossing a boundary that her parents had set for her as a teenager. It was educational and historical, familial and intimate. But going on the tour, for Nastya, was also an act of independent decision-making.

All of this - Nastya’s complex and multilayered experience - was enabled by the “dark tourism” that has popped up around Chornobyl. M. Gessen, in their Chernobyl review, dismisses these tours as “odd.” Just one word, even though they complain about the miniseries’ lack of attention to the disaster’s lingering consequences for Ukrainian society.

Of course, it’s not unusual for cultural critics to sneer at dark tourism - whether from a moral perspective as a form of voyeurism or from a class and racial perspective as a playground for privileged thrill-seekers.

No single tour experience is the same for all participants. And the meaning of any tourism hotspot locale is always dependent on the concerns that individual people bring to their visit, long before they buy a ticket or set foot on a plane or train. That’s what Nastya taught me. Dark tourism had hidden surprises. And to discover them, I’ll probably need to talk more with other people on my tours.