In early January, the Ukrainian Institute, a state agency for cultural diplomacy, issued a statement expressing “grave concern” directed at the Budapest International Documentary Film Festival (BIDFF). BIDFF organizers had decided to show a documentary film, Russians at War, by Canadian-Russian filmmaker Anastasia Trofimova. The Ukrainian Institute claimed that Trofimova had violated international law by embedding for seven months with a Russian brigade fighting in temporarily occupied Ukraine. Similar conflicts have dogged festival screenings of Russians at War in Toronto, Venice, Athens, Zurich, and elsewhere. Although the Ukrainian Institute demanded Russians at War be withdrawn from the festival, BIDFF organizers went on with the screening on January 26 and 28.

I was in Budapest for the BIDFF, and saw Russians at War. I also met Trofimova and had a chance to interview her. In early April, Balkan Insight published my analysis of these controversies and the debate about whether Trofimova is being “cancelled.” In that article, I did not talk about the film itself. Until now. Exclusive for subscribers to “At the Edges,” this is my review of one of the year’s most controversial documentaries.

Russians at War has earned some harsh assessments. Many have scoffed at Trofimova’s claim she filmed in secret. According to the story she told at BIDFF and elsewhere, she was riding on a train when she struck up a conversation with a soldier who invited her to film his unit. She then earned the commanders’ respect enough to ride to the front line, where she filmed for seven months on her own. And she did all this without the government or the military chain-of-command finding out.

If Russia’s government had approved of Trofimova’s work, even tacitly, it would no longer be accurate to call it “French-Canadian” production. It would also raise questions about whether she tailored the film’s content to avoid government censorship.

Latvian film scholar Elīna Reitere published a devastating, historically informed critique of Russians at War. I want to build on her review by focusing on Trofimova’s use of sound and the fim’s musical accompaniment. (The score was composed a French-Tunisian musician, Amine Bouhafa.)

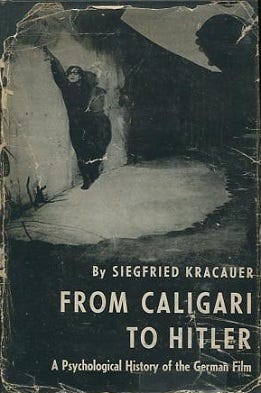

These elements have not been discussed in other reviews. Yet German Jewish film theorist Siegfried Kracauer once argued that film music plays a key role in turning “footage” into “propaganda.” In the epilogue to his 1947 book, From Caligari to Hitler, Kracauer wrote that a documentary purports to show what really happened, but it takes a soundtrack to turn this footage into “ideologically desired reality.” To understand how a film conveys a message - whether problematic or otherwise - we need to listen to it just as closely as we watch it.

All aboard to Moscow!

In our interview at BIDFF, Trofimova came across as earnest, collegial, and careful in her messaging and self-presentation. During a post-screening Q&A with the audience, she seemed rattled when people jeered one of her responses. To me, she was complimentary toward Sergei Loznitsa’s documentary about Ukraine, The Invasion. But perfect message discipline can become absurd if it’s too regimented. During our conversation, for example, Trofimova so insistently tried to “normalize” Russian society that it boggled common sense. She even invited me to visit her in Moscow. “If they don’t want you to come, they’ll just reject your visa application,” she said, “but if they let you in, you can do whatever you want.”

This whole spiel took me a second to process. Then I laughed in her face. “Like nothing bad has ever happened to American journalists in Russia?” I thought to myself.

In the end, Trofimova wasn’t offering me an actual invitation. She wasn’t serious about having me over for a little borscht. The point, in fact, was for me to repeat her invitation to others, and then to spread the message, the seed of an idea: Russia is, despite evidence to the contrary, a normal society.

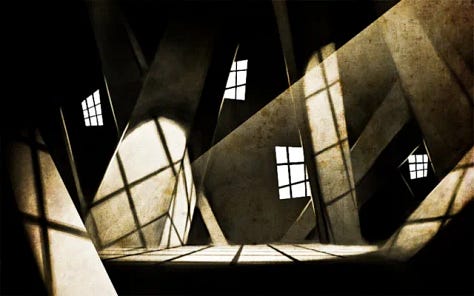

Critics have also called Russians at War a mediocre piece of filmmaking. Although the documentary has professional production qualities, it’s also superficial and trite. Nowhere more so than in its use of sound. In the film’s opening scene, Trofimova narrates in voiceover. She describes her chance encounter with the solder, whom she meets on a train to Moscow.

On the screen, we don’t see the soldier but rather what Trofimova is seeing out the window: a snowy suburban Moscow street, a row of unremarkable shops and advertisements. Then we see Trofimova’s face, reflected in the darkened window. Then her voice disappears, leaving only her face with accompanying sounds of the train whistle and the clickety-clack of rolling wheels.

For a train scene, these particular aural cues are deeply cliche. But aural cliches are useful, according to Siegfried Kracauer. In his 1960 book Theory of Film, Kracauer wrote that filmmakers use “recognizable” sounds to help audiences identify with the main characters:

“Generally speaking, any familiar noise calls forth inner images of its source as well as images of activities, modes of behavior, etc. which are either customarily connected with that noise or at least related to it in the listener’s recollection.”

In other words, recognizable sounds lure us into placing ourselves there in the action, alongside and with the film’s main characters.

But who are we supposed to identify with at this stage in Trofimova’s film? She is the first person we see up close, the first subject we’re asked to encounter, ponder, and perhaps understand. Before we ever get to the titular Russians at war, there is Trofimova. And the cliched sounds help us place ourselves in a familiar setting, alongside her, looking out the window as we travel through a snowy Moscow suburb.

We’re bound by our banality

The musical soundtrack, composed by the acclaimed French-Tunisian musician Amine Bouhafa, is also meant to invite us deeper into Trofimova’s experience. At BIDFF, I asked Trofimova what she wanted to accomplish with the film’s music. Characteristically, at first she voided her own agency. “It was just me sitting back and letting Amine do his magic,” she told me.

Then Trofimova started talking about wanting each scene to “transmit an emotion.” But whose emotion? Trofimova has repeatedly justified her project by saying that she wants to convey the soldiers’ real psychological experience. This is the film’s beating heart, she has said.

To me, she talked about the musical soundtrack that accompanies an early scene as she is getting ready to move out. “When I’m supposed to be going to the front and you have this long ‘hmmm,’ it was the fear that I felt going into the complete unknown. I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

But for all this effort to dial up the anticipation, Russians at War mostly fails. It’s a long movie: over two hours. I was bored, and especially by the music. Trofimova (and Bouhafa) use two modes to illustrate the action. 1) Rising quarter notes played by shrill, screeching strings. 2) A solo plucked guitar.

Here is a recording of the end credits music, an example of #1.

The string sections are an unimaginative homage to some of the eerier music from Chernobyl, the HBO TV series, composed by Hildur Guðnadóttir.

#2: This musical clip is from a scene that Trofimova shot through the window of a Russian military vehicle. She’s riding through a Ukrainian town that Russian forces have destroyed, and she’s filming the ruins as they pass by.

The guitar, with its classical spaghetti Western feel, is the most problematic musical accompaniment. It puts Trofimova at a distance from the devastation, like she’s a cowboy ambling through some picturesque but ultimately alien landscape. As if, like these cowboys, she’s not an agent of a conquering power but rather a hero stumbling onto an ahistorical injustice and then saving the day.

In the end, the musical atmosphere of Russians at War just doesn’t work. The string and guitar sections do not gel. It’s like a fusion-restaurant gone wrong, or a festival lineup programmed solely on the basis of band names. The movie soundtrack lives somewhere between haunted house and lonesome cowpoke.

Is it a moral problem that the film is really about Trofimova’s experience, the heroic journey of a wartime filmmaker, rather than everyday Russian soldiers? Every portrayal of an unfamiliar social world is, to some extent, an imaginative reconstruction of someone else’s experience. If we’re talking about people whose lives are different in some way, we’re always guessing, projecting, imagining. This guesswork always begins by recognizing something that we already know from our own experience.

But truly insightful art takes a next step by asking a critical question: Is it okay to make this comparison between what I’m seeing and what I know? Insightful art probes the limits of imaginative reconstruction. And that’s what was missing from Trofimova’s film. Her narcissism doesn’t allow for any acknowledgement of the otherness of these soldiers. Surely, there are aspects of their lives that don’t fit in the straightened contours of this genre, which you might call a “drama of humanizing the stranger.”

At the height of the Enlightenment, philosophers used to say that reason bound us all together. Trofimova seems to believe that melodrama, soap, and self-indulgent tenderness are the human essence. Trofimova wants us to weep, laugh, gripe, lament, and mourn along with her - and by imaginative extension her Russian soldiers - and thus to discover our shared human kinship. Affect has replaced rationality in the humanistic imagination.

But dreariness is what really binds us together as human beings. We’ve got more in common in our capacity to be boring than we have in any ashes-and-sackcloth melodrama.

At the end of the film, for example, Trofimova films family members weeping at their soldiers’ graves. But she doesn’t linger, even though she is clearly willing to test her audience’s patience with such a long film. (With me, she even joked self-consciously about her film’s two-hour run time.) She could have, for example, accompanied these families through the banal routines of mourning: The boring, repetitive stories. The cliches about lost youth. And then, much later, scraping the musty wax from the headstone and carrying away the dull blooms. Real devotional work lies in these unremarkable gestures.

But Trofimova can’t see the humanizing potential of the unremarkable. Rather than lingering, she cuts quickly from one funeral to another, and portrays only the keening, the weeping, the most gripping parts of the mourning ritual. She’s afraid her audience - who by now expect humanistic melodrama from the people on the screen - will become distracted if the mourners get on with the real - and really banal - work of remembrance. More than anything, Trofimova fails to portray her subjects as human beings because she fails to make them boring.